As the digitization of life intensifies in the era of lockdowns, it is urgent to think about how the “Digital Revolution” is shaping a new economic order that extends the destructive hold of industrial capitalism over nature and society. Two recent works discussed here by economist Hélène Tordjman help us move forward on this path.

The digitization of economic and social activities is a fundamental movement, which affects all sectors and takes several forms: coordination tasks, even decisions, are entrusted to algorithms; at all stages of production, machines are interconnected by the Internet of Things; finally, data becomes an important raw material, provided by consumer-citizens as soon as they are on the Internet, social networks, or use “connected objects”. This data feeds the artificial intelligence disseminated everywhere, and opens a new field for the valuation of capital. In particular, they allow GAFAM to control the advertising markets, and to invent new commercial services based on an increasingly intimate knowledge of our actions, our preferences and even our emotions.

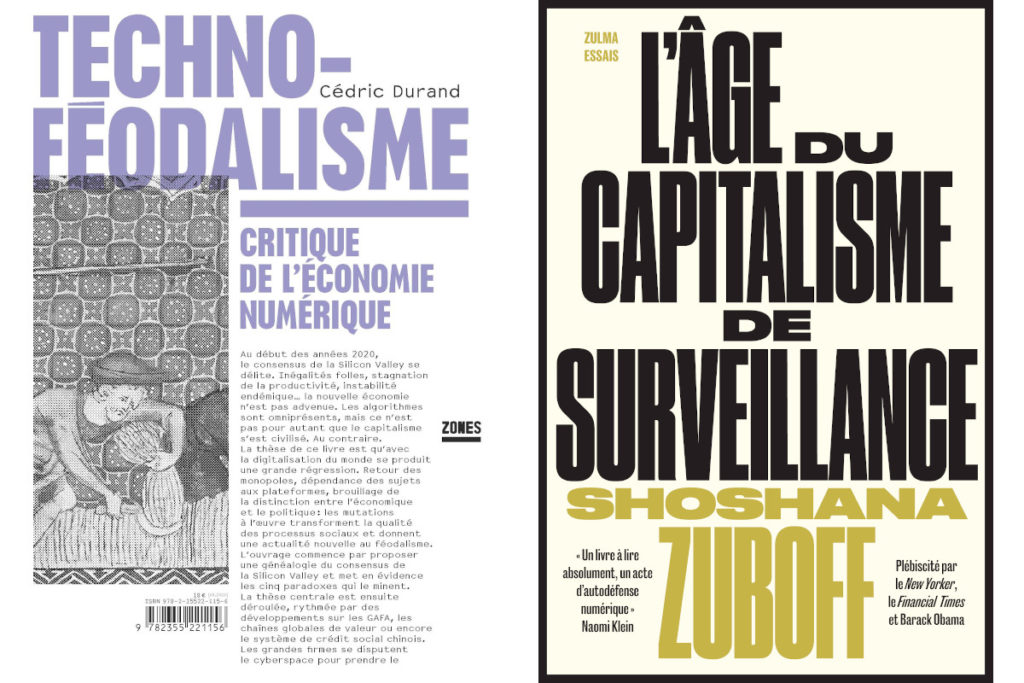

Two recent books offer interpretations of these developments. In The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, sociologist Shoshana Zuboff analyzes how Google, Facebook, and the like have succeeded in turning the traces each of us leaves on our way through cyberspace into hard cash. She sees the advent of a “rogue capitalism” based on the appropriation of our private data, and warns of the dangers of such appropriation. The economist Cédric Durand interprets these changes within a Marxist framework. He points out in particular two phenomena which would presage a return to a certain form of feudalism, a “feudal regression”: the dismantling of the wage system and the replacement of contractual relations of subordination by relations of dependence; and the growing share of rents in corporate profits1.

While these two authors each bring to light indisputable facts, their interpretations of them do not seem entirely convincing, for the same reason: a lack of analysis of the technical phenomenon. Here I mean technique in the sense of Jacques Ellul, the domination of a mode of action geared towards the search for maximum efficiency in all things2. More precisely, “Technique is the set of absolutely most effective means at a given time. This makes it possible to take down the Technique of the machine, because there are indeed many other techniques than those which relate to the machines (for example the sports techniques) 3 “.

In this sense, technique also encompasses modes of organization, certain areas of law, and what Ellul calls “human techniques”, psychology, advertising, propaganda, aimed at social efficiency. So everything that comes under social engineering belongs to the technical realm. This global perspective on the technical phenomenon resonates with Max Weber’s vision of capitalism seen as a great process of rationalization and the domination of a rational mode of action in the end, emblematic of the engineering spirit. If we adopt this point of view, contemporary developments do not signify a change of regime, but a deepening of industrial capitalism and its extension to new areas, more and more calculation and control, a desire to control nature and the ever-expanding society. ”

THE IDEOLOGY OF SILICON VALLEY

In the first chapter of his book, Cédric Durand traces the genesis of the “Silicon Valley consensus”. This consensus was formed in the 1990s, drawing both on the Californian libertarian ideology of the 1960s and 1970s, and that of neoliberalism, giving primacy to the individual and his freedom to conduct business. Thus, the beginnings of the Internet offered a glimpse of a more “horizontal” world, where everyone’s knowledge would be accessible to everyone, where individuals would emancipate themselves from the tutelage of the state and large companies. The Internet would allow decentralized economic and social organization and free exchanges, a utopia still present in free software circles. However, it was necessary to become disillusioned fairly quickly. By the mid-1990s, under President Bill Clinton, the financial prospects for new information and communication technologies became very attractive. Capital is pouring in, thousands of start-ups are created, this is the boom of the “new economy”. Several think tanks and foundations then play a major role in the dissemination of this digital entrepreneurial spirit, including the Progress and Freedom Foundation, “a key player in the crystallization of a right-wing ideology associated with the digital revolution4”. In 1994, this foundation published an important text, A Magna Carta for the Knowledge Age, which proclaimed the end of the pre-eminence of material wealth in favour of the immaterial wealth that is knowledge. Thanks to the Internet, a new territory is opening up, still without rules or laws, which reactivates the American myth of the Frontier, of a virgin space to be conquered. Wired magazine, created in 1993 in San Francisco, also conveys this right-wing libertarian ideology called libertarianism.

This new area of freedom, cyberspace, must remain free, without the intervention of a federal state which is still prone to bureaucracy. For example, we can read in the Magna Carta for the Knowledge Age that “if there is an industrial policy for this new knowledge age, it must focus on removing the barriers that hinder competition and promote deregulation massive telecommunications and IT sector. The advent of cyberspace means the death of all centralized organizations and bureaucracy. Cyberspace is America’s last frontier […] America, after all, remains the land of individual freedom, and that freedom extends to cyberspace ”5. The reference to the process of creative destruction popularized by Joseph A. Schumpeter is very often present, as is that to Ayn Rand, a writer singing the praises of freedom and competition, the only one capable of rewarding “creative spirits” and of punishing. the “assisted6”.

Besides the glorification of individualism and competition, the other pillar of the ideology of Silicon Valley is the sacralization of technique, the belief that a more satisfactory social organization will result from scientific and technical progress, in particular from artificial intelligence. This makes it possible to automate a growing number of actions and decisions, making the economic and social system calculable and predictable, like a large machine running smoothly. This representation is not new, but the benchmark machine today is no longer mechanical but cybernetic. Alain Supiot perfectly shed light on this shift from government to that of “governance by numbers”: “the governing machine is no longer designed on the model of the clock but on that of the computer. Acephalous machine where power is no longer localizable and where regulation replaces regulation and governance, government, […], which is supposed to regulate itself like a biological organism or a computer7 “

For Shoshana Zuboff, the main source of what she calls “the utopia of certainty”, this idea that social progress requires a reduction in uncertainty and surprises, is to be found in the work of BF Skinner and his “radical behaviourism”. By going fast, human beings are not much different from pigeons or rats. They overestimate their free will and underestimate the evolutionary determinants and environmental stimuli that make them act. An efficient organization of society can thus be achieved by a good structure of these stimuli, which behavioral economics has more recently developed under the name of nudge8. More fundamentally, in the age of surveillance, a large number of new technologies can be used to build an efficient society: artificial intelligence interpreting people’s behavioral data, sensors of all kinds (including facial recognition) , generalized tracing (as we can observe it in the Chinese system of social credit9)…, all technologies of social control.

In this vision of society, which Zuboff describes as “instrumental”, “social phenomena are only aggregations of billions of small transactions between individuals” (p. 572), and it is a question of “creating a nervous system. for humanity ”(p. 568). She quotes here one of the gurus of this movement, Alex Pentland, of the MIT MediaLab, for whom the digitization of all social relations, the extension of this “ubiquitous computing” makes it possible to approach this ideal of control. One can find roots of such a hyper-individualistic and technical perspective on the social as early as the 19th century, in particular with Jeremy Bentham, champion of social engineering. In other words, and as Alain Supiot reminds us, this desire for control is not new. However, the technological surge of recent decades has provided it with tools of unparalleled power. It is furthermore promoted by an ideology alongside which both Shoshana Zuboff and Cédric Durand have surprisingly passed, that of transhumanism. The latter, which aims to “increase” human and social performance through science and technology, was also born in Silicon Valley at the end of the 1980s, and is an integral part of the “consensus”. The utopia of a self-regulated society thanks to technosciences appears as such in a report by the National Science Foundation from 2002, which describes how the convergence of new sciences such as nanotechnology, biotechnology, information and cognitive sciences (the “NBIC convergence”) can found a “new renaissance10”, where “technology is a real alternative to politics11”. One of the most recent manifestations of this scientific and cybernetic social utopia is that of the Great Reset, the “reset” of the world economy following the crisis caused by the coronavirus, proposed by the Davos Economic Forum.

VALUE CREATION IN THE DIGITAL ECONOMY

“If it’s free, then you are the product.” This is how the business model of digital platforms was summed up at the start of their expansion. Shoshana Zuboff shows that it is not. We are not the product, but the raw material, the source of the valuable data from which these platforms make their products. She sheds light on the existence of what she calls a “behavioural surplus” made up of all the data we leave behind when we go online. Thanks to the increasingly sophisticated algorithms used by GAFAM, this data is interpreted to predict our behaviour, which in turn allows advertisers to target us in the most personalized way possible. “In 2016, 89% of parent company Alphabet’s revenue came from Google’s targeted advertising campaigns.” In the same year, Google and Facebook “together assumed nearly 90% of the growth in advertising spending12”.

Advertisers aren’t the only customers, these “markets for future behaviour” are of interest to many other industries. Hal Varian, author of popular microeconomics textbooks and senior economist at Google, sees it early on: he “addresses the example of ‘vehicle control systems’ which he recognizes as paradigmatic. When a motorist no longer pays the monthly payments on his car loan, it is much easier today to order the vehicle’s control system to block the engine and send the contact details of the car in order to make recovery possible ‘. Insurance companies, he notes, can also rely on these systems to judge a driver’s caution. ”13 S. Zuboff’s book is very rich and lists dozens of examples of how Google and Co are developing strategies to collect an increasing amount of personal data, aided in this by advances in nanotechnology and technology. artificial intelligence. Facial recognition software, for example, makes it possible to analyse the emotions of those who receive the advertisements, in order to adjust the latter even more finely. Autonomous cars, and connected objects more generally, are real data traps. With the launch of the Pokemon Go game in 2016, thousands of children and so-called adults were sent to search for these conveniently hidden virtual creatures at McDonald’s or any other retailer willing to pay to welcome them. Self-contained vacuums map the plans of the homes where they operate. Wearables, connected objects that you wear to measure the number of steps you take or your heart rate, connected mattresses (yes, it does exist) collect more and more intimate data, to such an extent that after The Internet of Things appears the Internet of Bodies… These mounds of data allow us to train algorithms, which therefore become more and more powerful in tracking our lives and collecting new data , in a spiral with no other end than that which the law could put there.

Zuboff insists precisely on the “psychic numbness” which makes us accept such a loss of autonomy and free will. Nevertheless, as C. Durand points out, his perspective is very individualistic, centered on the dispossession of the consumer by ill-intentioned capitalists. She advocates a return of governments in these matters, as if the state were a guarantee. The Marxist perspective of C. Durand makes him embrace the phenomenon in a more global way, by analyzing the global value chains from the beginning to the end of production, not in its only last stage of consumption, and not only those of GAFAM.

The concept of a global value chain captures the process of producing a good through the technical, geographic and fiscal fragmentation implemented by large firms in the globalized world that is ours, a fragmentation greatly helped by the digitization of activities and the remote coordination that it allows. It makes it possible to identify the stages of production that generate the most value. Various studies of these value chains show that today, value is essentially created upstream, when the product is designed, or right downstream, when it is sold. Manufacturing is no longer a real source of value, which is why it is generally outsourced to countries in the South with low labor costs and reduced social and environmental legislation. Apple, for example, is a firm without a factory, all manufacturing is subcontracted. The design and sale are enhanced by intellectual property rights, patents, designs and models, algorithms and databases, brands. “The concentration of value at the extremes of the chain is the expression of a process of intellectual monopolization at the end of which economic power is concentrated in a few strategic sites14”. These strategic sites are those where the most data is extracted and analyzed by manufacturers to improve “the user experience, design targeted advertising or sell personalized services15”. Data is now a fundamental raw material in the process of capital appreciation, and its exploitation gives rise to different types of rents.

Cédric Durand distinguishes four (chapter three). The first derives from the monopolization of knowledge deriving from intellectual property rights. It should be noted that the intellectual property regime has tightened considerably since 1980 and the beginnings of neoliberalism, and extends to scientific information in all its diversity: software and algorithms, databases, but also to the genetic information of living things, from microorganisms to humans, including animals and plants. A growing number of “intangible” things can now be appropriated. The second is a “natural monopoly” rent, in situations where it is more economical for a single firm to produce a good or service rather than several competing firms. This is the case with rail networks, but also with most network industries, such as the telephone industry. It is based among other things on “network complementarities”: Apple does not sell only iPhones, but all the products of the “Apple ecosystem”, operating system, applications, iPods and other tablets, all compatible with each other, and incompatible with competitors’ products. The third type of annuity is the “intangible differential annuity”, which arises from the difference in returns to scale between tangible and intangible assets. The latter being essentially knowledge, know-how and information, they are reproducible at a marginal cost which tends towards zero, which is not the case with tangible assets. Finally, C. Durand defines a “dynamic innovation rent”. The large firms that control global value chains organize the integration of productive processes. “Information accumulates in very specific places where the integration functions are concentrated.” These firms “centralize the data. However, these data are an essential raw material for modern research and development processes: thanks to them, it is possible to identify weaknesses, identify sources of improvement, virtually test innovative solutions16 “. Who controls this data has an advantage in the frenzied technological competition between big companies and big powers. In addition, the control of the material infrastructures necessary for the circulation and storage of data (submarine cables, electromagnetic frequencies, 4G and soon 5G antennas, data centers, cloud, etc.) confers an absolutely strategic position.

The digital economy therefore does not cover only the digital services offered by the major platforms. It is the entire productive system that is gradually digitized, a process that generates a change in the organization of value chains (that is to say in the international division of labor) and therefore in the places where value is created and appropriate.

SURVEILLANCE CAPITALISM, TECHNO-FEODALISM, OR DEEPENING OF TECHNOSCIENTIFIC CAPITALISM?

With the extension of surveillance, capitalism is crossing a new threshold. As Zuboff writes, “Industrial capitalism has followed its own logic of ‘shock and amazement’, seizing nature and conquering it in the name of the interests of capital; what surveillance capitalism now has its sights on is human nature ”17. All the digital devices aimed at extracting our personal data to better predict and guide our behavior form a ubiquitous infrastructure in which we are all caught, an infrastructure that Zuboff calls Big Other. This impersonal power mirrors our behaviors from another abstract point of view, to the same place as the Skinnerian experimenter guiding his rats through a maze with the right stimuli. And this in an essentially advertising perspective, as in the game of Pokemon Go.

However, publicity and propaganda in the service of social engineering aimed at controlling the masses have existed for more than a century. Their means were different, more artisanal, and have certainly been revolutionized by digital technology, but there is no radical novelty here, it seems to me. Zuboff sees the origin of surveillance in the desire of a few “rogue capitalists” to enrich themselves at our expense, but thinks that other, more respectful uses of digital technology were possible, and that States would be able to encourage them. by limiting the power of GAFAM. In other words, it is not the digitization of all human activities that would be bad, but the use that is made of it.

The belief in the neutrality of the technique is also shared by Cédric Durand18. The place of technique is a blind spot in Marxist approaches, all centered on what happens at the level of the appropriation of production, and not of its precise technical forms. This belief is at the heart of technical ideology and legitimizes most technological innovations. The atom promised inexhaustible energy, the bomb was only an unfortunate development. Biotechnology will produce new plants and new drugs, improving human health and solving the problem of world hunger, while experiments with genetically modified babies are the work of rogue scientists. Likewise, facial recognition is of great help in the fight against crime, and does not have to be used to hunt down honest citizens. These commonplaces testify to a lack of understanding of the technical phenomenon. As Jacques Ellul analyzes it forcefully, modern technique is characterized by its insecurity: it forms a system, a whole, and it is impossible to circumscribe certain parts to separate them from the others. On the other hand, its dynamic is one of blind self-increase, of a subjectless process developing in response to the questions it asks itself. Finally, it tends to be autonomous, that is to say, closed to any moral questioning, deploying itself in the sole dimension of the search for maximum efficiency. This autonomy is of course not complete, the entanglement of power games, ideologies and institutional funding priorities directing the technological paths that will ultimately prevail19.

Thus, the digitization of society and the economy is producing an increasing amount of data. What are they going to be used for? New algorithms performing new functions are developed and generate new uses. As the computing power continues to grow, infrastructure must be developed: from 3G to 4G, 5G, and soon 6G… This exponential volume of data makes it possible to “train” algorithms, which become more efficient in applications. more and more extensive, without ever questioning the order of meaning slowing this dynamic, and digitization continues. But this is not specific to the digital economy, as Zuboff and Durand write. It has been like this from the earliest days of the industrial era, until today’s NBIC convergence. “Anything technical, without distinction of good or bad, is necessarily used when you have it in your hands. This is the major law of our time20 ”. Not seeing this leads, it seems to me, the two authors to identify a change of regime where there is continuity and deepening of an already existing dynamic. Moreover, it is because technique is not neutral that it so disrupts our lives: it brings to light with it practices and social relations that are inextricably linked to it. Developments in the latter would be different if biotechnologies had developed on a large scale before information and communication technologies. The horizon would be Brave New World and Gattaca rather than 1984. But in both cases, calculation, predictability and control, the historical necessity of industrial capitalism.

Undoubtedly because of his Marxist perspective, Cédric Durand gives a great place in his developments to the transformations of work, while Shoshana Zuboff sees the human being primarily as a consumer. Following other authors, such as Alain Supiot, he sheds light on the changes brought about by digitization in labor relations, in particular in the platform economy, what is called “uberization”. The workers on these platforms are no longer bound to their employer by an employment contract but by subcontracting relationships. They are legally independent (therefore assume the risks associated with their activity), but must donate part of their earnings to the platform that allows them to work. Thus, from subordination, the working relationship shifts to dependence. “In the case of Uber drivers, this leads to a paradoxical situation, where the aspiration to autonomy comes up against the extremely strong hold of the platform on the activity: real-time control of the course of the race, submission the evaluation of passengers, opacity in setting prices, prohibition on taking customer details, incentive bonuses aimed at building driver loyalty or increasing the offer in certain areas, penalties that can go as far as deactivating the account, etc. 21 ”. The asymmetry of the working relationship is still there, but it has changed in nature: “the platforms are like fiefdoms”, and “the subjects are attached to the digital soil”. This is one of C. Durand’s major arguments for identifying “feudal regression”.

The other main argument put forward for qualifying the contemporary regime as techno-feudalism concerns the nature of profits. As mentioned, due to the evolution of global value chains, the share of rents in corporate profits is steadily increasing. In a Marxist view based on labor value, corporate profit results from the extraction of surplus value in the production process, part of the work, the “surplus labor”, not being remunerated. This, according to Marx, is the heart of the mechanism for the valuation of capital in the capitalist mode of production. Rent, on the contrary, produces value without production. It arises from the ownership of capital, material and / or intellectual, and does not find its origin in manufacturing work. Taking this perspective, it is not surprising that the author interprets the growing preeminence of rents over productive profits as a sign of a return to a form of feudalism.

However, if we move the point of view, this interpretation can be debated. Since the beginning of the 1980s and the advent of a capitalism regime described as financialized by the authors of the School of Regulation22, financial profits, which have the nature of a rent, have become more important than profits. productive, even for non-financial firms. To the four major types of annuity identified by Cédric Durand, we should therefore add the category of financial annuities, the overall value of which is much greater. However, these rents generated by the ownership of capital do not signify a return to feudalism, but rather an increase in the power of the owners of capital to the detriment of the workers. In other words, they testify to a deepening of capitalism: a change in the regime of accumulation but not of the mode of production.

Finally, against the thesis of a return to feudalism, and besides the fact that the idea of a “return” goes against a temporal vision recognizing irreversibilities, let us recall three of its linked features. The first is that feudal societies were societies of orders, of castes, where the positions of human beings were fixed by the laws of their birth. As Louis Dumont has shown, these were holistic societies: social relations were codified by statutes and traditions, crossed by multiple memberships of various communities (of orders, religious, profession), where the an individual in the modern sense of a subject acting “freely” did not exist as such23. The second concerns the motive of human action. It is only with the advent of capitalism that rational action in the end comes to dominate, and with a very narrowly defined end: monetary profit. The pursuit of material interest was previously considered to be unreliable, feudal societies valued the pursuit of beauty and glory on the battlefield, certainly not the pursuit of profit. Finally, the third fact refers to the place occupied by technique. The definition given by Jacques Ellul, as a principle of maximum social efficiency, allows us to broaden the perspective and understand how the emergence of individualism and the social atomization that followed were conditions for development. of modern technology. Regarding the Industrial Revolution, he writes: “There is no freedom of groups, but only of the isolated individual. […] This atomization gives society the greatest possible plasticity. And this is also, from the positive point of view, a decisive condition of the technique: it is in fact the rupture of social groups that will allow the enormous displacements of men at the beginning of the 19th century which ensure the human concentration required by modern technique25 ”. This atomization has continued to deepen, resulting in what sociologist Zygmunt Bauman calls a “liquid society”. Such fluidity is both permissive and created by technological innovation that constantly upsets the conditions of existence of human beings. This perpetual movement is contrary to the stability of orderly societies like European feudalism.

Thus, an Ellulien look at the technical phenomenon rather leads to register the digital upheaval in a longer dynamic of continuous technical acceleration since the end of the 18th century, the ultimate change of contemporary capitalism. However, whatever the differences in interpretation of current phenomena, the works of Zuboff and Durant are very rich and provide essential reflection for understanding the evolutions of contemporary capitalism.

Source:https://www.terrestres.org/2021/05/17/economie-numerique-la-mue-du-capitalisme-contemporain/